Battle of Taranto

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The naval Battle of Taranto took place on the night of 11–12 November 1940 during World War II. The Royal Navy launched the first all-aircraft naval attack, ship-to-ship in history, flying a small number of torpedo bombers from an aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean Sea to attack the Italian Navy's battle fleet at anchor at the harbor of Taranto, utilizing aerial torpedoes, in spite of the shallowness of the harbor. The devastation wreaked by the British carrier-launched aircraft on the large Italian warships was the beginning of the rise of the power of naval aviation, over the big guns of battleships.

Contents |

Origins

Long before the First World War, the Italian Royal Navy's First Squadron was based at Taranto. In that period, the British Royal Navy developed plans for countering the power of the Italian fleet. Blunting the power of any adversary in the Mediterranean Sea was an ongoing exercise. Plans for the capture of the port at Taranto were considered as early as the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935.[1]

During 1940–41, Italian Army operations in North Africa, based in Libya, required a supply line from Italy. The British Army's North African Campaign, based in Egypt, suffered from much greater supply difficulties. Supply convoys to Egypt had to either cross the Mediterranean via Gibraltar and Malta, and then approach the coast of Sicily, or steam all the way around the Cape of Good Hope, up the whole east coast of Africa, and then through the Suez Canal, to reach Alexandria. Since the latter was a very long and slow route, this put the Italian fleet in an excellent position to interdict British supplies and reinforcements.

The British had won a number of actions, considerably upsetting the balance of power in the Mediterranean. Following the theory of a fleet in being, the Italians usually kept its warships in harbor. The Italian fleet at Taranto was powerful: six battleships (five battleworthy), seven heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and eight destroyers, making the threat of a sortie against British shipping a serious problem.

During the Munich Crisis of 1938, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, was concerned about the survival of the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious in the face of Italian opposition in the Mediterranean. Pound ordered his staff to re-examine all plans for attacking Taranto.[1] He was advised by the captain of Glorious, Arthur L. St.G. Lyster, that her Fairey TSR Swordfish were capable of a night attack, using aerial torpedoes. Indeed, the Fleet Air Arm was then the only naval aviation arm capable of it.[1] Pound took Lyster's advice, and he ordered training to begin. Security was kept so tight there were no written records.[1] Just a month before the war began, Pound knowingly advised his replacement, Admiral Andrew Cunningham, to consider the possibility. Thus came to be known as "Operation Judgement".[2]

The fall of France and the consequent loss of the French fleet in the Mediterranean (even before "Operation Catapult") made redress essential. The older carrier, HMS Eagle, on Cunningham's strength, was ideal, possessing an air group consisting entirely of Swordfish, very experienced. Three Sea Gladiator aircraft were added for the operation.[1] Firm plans began to be drawn up after the Italian Army halted at Sidi Barrani, which freed up the British Mediterranean Fleet.[1]

Judgement was just a small part of the over-arching "Operation MB8".[1] It was originally scheduled to take place on 21 October 1940, Trafalgar Day, but a fire igniting in a 60 Imperial gallon (270 liter) auxiliary fuel tank of one Swordfish, one which would replace its third crewman to extend the flight range enough to reach Taranto, led to a more serious fire that destroyed two of the Swordfish.[1] Then Eagle suffered a breakdown in her fuel system,[1] so she was eliminated.

The brand-new carrier, HMS Illustrious, became available in the Mediterranean, based at Alexandria. (Note: her battle group was under the command of Rear Admiral Lyster,[1] who had created the plan to attack Taranto. The Illustrious took on board five Swordfish from the HMS Eagle, and the Illustrious would have to launch the air raid alone.[3]

The complete naval task force consisted of the Illustrious, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and four destroyers. The 24[1] attack Swordfish came from the 813 Naval Air Squadron, the 815 Naval Air Squadron, the 819 Naval Air Squadron, and the 824 Naval Air Squadron. The small number of attacking warplanes raised concern that operation "Judgement" would only alert and enrage the Italian Navy without achieving any significant results.[1] The Illustrious also had the 806 Naval Air Squadron of fighter planes on board to provide air cover for the task force.

Half of the Swordfish were armed with aerial torpedoes as the primary strike aircraft, with the other half carrying aerial bombs and flares to carry out diversions.[1] These torpedoes were fitted with Duplex magnetic / contact exploders, which were extremely sensitive to rough seas,[1] as the later attacks on the Kriegsmarine battleship Bismarck later showed. There there were also worries that the aerial torpedoes would bottom out in the harbor after being dropped.[1] The loss rate for the bombers was expected to be fifty percent.[1]

Several reconnaissance flights by Martin Maryland bombers (of the RAF's No. 431 General Reconnaissance Flight)[1] flying from Malta confirmed the location of the Italian fleet. These flights produced photos on which the intelligence officer of the Illustrious spotted previously unexpected barrage balloons, and the attack plans were changed accordingly.[1] To make sure that the Italian warships had not sortied, the British also sent over a Short Sunderland flying boat on the night of 11 November, just as the carrier task force was forming up about 170 miles (315 kilometers) away from Taranto harbor, off the Greek island of Cephalonia. This reconnaissance flight alerted the Italian forces in southern Italy, but since they were without any radar sets, they could do little but wait for whatever came along. The Italian Navy could conceivably have gone to sea in search of any British naval force, but this was distinctly against the naval philosophy of the Italians during January 1940 – September 1943, when Italy simultaneously surrendered to the Allies and declared war on Germany and Austria.

The complexity of "Operation MB8", with its various forces and convoys, succeeded in deceiving the Italians into thinking only normal convoying was underway. Thereby this contributed to the success of the Judgement operation.[1]

The Attack

|

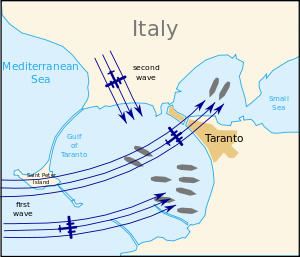

The first wave of 12 Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers left the Illustrious just before 21:00, followed by a second wave of nine bombers about an hour and a half later. The first wave, which consisted of a mixture of six armed with aerial torpedoes, and six armed with aerial bombs, was split into two sections when three of the bombers and one torpedo bomber strayed from the main force while flying through thin clouds. The smaller group continued flying to Taranto independently. The main group of planes approached the harbor at 22:58. A flare was dropped east of the harbor and the flare dropper and another aircraft made a dive bombing attack to set fire to oil tanks. The next three aircraft, led by Lt Cdr K. Williamson, RN of 815 Squadron, attacked over San Pietro Island, and struck the battleship Conte di Cavour with a torpedo that blasted a 27-foot hole below her waterline. Williamson's plane was shot down by flak from the Italian battleship.[4] The two remaining aircraft in this sub-flight continued, dodging the balloon barrage and receiving heavy anti-aircraft fire, to press home an unsuccessful attack on the battleship Andrea Doria. The next sub-flight of three attacked from a more northerly direction, attacking the battleship Littorio, hitting it with two torpedoes and launching one torpedo at the flagship Vittorio Veneto which failed to hit its target. The bomber force led by Capt O. Patch RM next attacked. Their pilots found the targets difficult to identify but they attacked two cruisers from 1,500 ft, followed by another aircraft which dropped its bombs across four destroyers.[3]

The second striking force of nine aircraft was now approaching, two of the four bombing aircraft also carrying flares and the remaining five carrying torpedoes. One turned back with a problem with its auxiliary fuel tank, and one aircraft launched 20 minutes behind the others after requiring emergency repairs to damage from a minor taxiing accident. Flares were dropped shortly before midnight. Two aircraft aimed their torpedoes at the Littorio, one of which hit home. One aircraft, despite having been hit twice by anti-aircraft fire, aimed a torpedo at the Vittorio Veneto but that torpedo missed its target. One aircraft hit the battleship Caio Duilio with a torpedo blowing a large hole in her hull and flooding both of her forward magazines. The aircraft flown by Lt G. W. L. A. Bayly, RN was shot down by the heavy cruiser Gorizia[4] while following the attack on the Littorio, this being the only aircraft lost from the second wave. The final aircraft to arrive on the scene 15 minutes behind the others made a dive bombing attack on an Italian cruiser despite heavy antiaircraft fire, and it made a safe getaway, returning to the Illustrious at 0239 hours.[3]

Of the two aircraft shot down, the two crew members of the first plane were taken prisoner, but the other two fliers were killed.[5]

Aftermath

The Italian fleet had suffered heavily, and the next day the Regia Marina transferred its undamaged ships from Taranto to Naples to protect them from similar attacks.[3] Repairs to the Littorio took about five months and to the Caio Duilio six, but the Conte di Cavour required extensive salvage work and her repairs were incomplete when Italy simultaneously surrendered in 1943 and declared war against Nazi Germany.[6] The Italian battleship fleet lost about half of its strength in one night. The "fleet-in-being" also diminished in importance, and the Royal Navy increased its control of most of the Mediterranean. This control of the sea, with the help of the U.S. Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy during 1943–44, was to become complete, for all practical purposes. (Excepting only the Turks, who were neutral).

Despite this serious setback, the Regia Marina had adequate resources to fight the Battle of Cape Spartivento on 27 November 1940. However, the British decisively defeated the Italian fleet a few months later in the Battle of Cape Matapan, near Greece, in March 1941.

Aerial torpedo experts in all modern navies had previously thought that torpedo attacks against ships must be in deep waters, of at least 30 m (100 ft) deep. The Taranto harbor had a water depth of only about 12 m (40 ft). However the Royal Navy used modified torpedoes dropped from a very low height.

The Imperial Japanese Navy's planning staff carefully studied the Taranto attack when planning their aerial torpedo attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The air attack on Pearl Harbor was a considerably larger operation than Taranto with six Imperial Japanese fleet fleet carriers, each one carrying an air wing that was more than double the planes that a British carrier had. It hence resulted in far more devastation, sinking or disabling seven American battleships, and seriously damaging other warships. However, it can be argued that this air attack on the United States Fleet did not alter the balance of power in the Pacific in the same way that the attack on Taranto did in the Mediterranean Sea.

The old and slow battleships of the American fleet turned out to be far less useful in the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, compared with battleships in the narrow confines of the Mediterranean. Also, the leaders of the U.S. Navy was forced to modernize their thinking: the new dominant capital ship of naval warfare had become the aircraft carrier. The U.S. Navy had six fast, modern fleet carriers available to go to war against the Japanese Navy, and all six of them did – with four of them being sunk. Very importantly, the U.S. Navy had several of the new, well-designed Essex class aircraft carriers already under construction, and these started to win the war against Japan in 1943. The new, powerful aircraft carriers of the U.S. Navy were instrumental in the counterattack against the Empire of Japan.[7] [8]

Citations

Notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 Stephen, Martin; Grove, Eric (Ed) (1988). Sea Battles in Close-up: World War 2. Volume 1. Shepperton, Surrey: Ian Allan. pp. 34–38. ISBN 0711015961.

- ↑ "Taranto 1940". Royal Navy official web site. royalnavy.mod.uk. http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/server/show/conWebDoc.1593. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Sturtivant, Ray (1990). British naval aviation: the Fleet Air Arm 1917–1990. London: Arms & Armour Press Ltd. pp. 48–50. doi:358.4/00941. ISBN 0853689385.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 La Notte di Taranto (Italian)

- ↑ Australian Naval Aviation Museum (1998). Flying Stations: a story of Australian naval aviation. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. p. 23. ISBN 1 86448 846 8.

- ↑ Playfair, Vol I, p, 237

- ↑ Borch, Frederic L.; Martinez, Daniel (2005). Kimmel, Short, and Pearl Harbor: The Final Report Revealed. Naval Institute Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 1591140900.

The Dorn report did not state with certainty that Kimmel and Short knew about Taranto. There is, however, no doubt that they did know, as did the Japanese. Lt. Cdr. Takeshi Naito, the assistant naval attaché to Berlin, flew to Taranto to investigate the attack firsthand, and Naito subsequently had a lenghty conversation with Commander Mitsuo Fuchida about his observations. Fuchida led the Japanese attack on 7 December 1941.

- ↑ Gannon, Robert (1996). Hellions of the Deep: The Development of American Torpedoes in World War II. Penn State Press. p. 49. ISBN 027101508X.

A torpedo bomber needed a long, level flight, and when released, its conventional torpedo would plunge nearly a hundred feet deep before swerving upward to strike a hull. Pearl Harbor depth averages 42 feet. But the Japanese borrowed an idea from the British carrier-based torpedo raid on the Italian naval base of Taranto. They fashioned auxiliary wooden tail fins to keep the torpedoes horizontal, so they would dive to only 35 feet, and they added a break-away "nosecone" of soft wood to cushion the impact with the surface of the water.

References

- Playfair, Major-General I.S.O.; with Stitt, Commander G.M.S; Molony, Brigadier C.J.C. & Toomer, Air Vice-Marshall S.E. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO:1954]. Butler, J.R.M. ed. Mediterranean and Middle East Volume I: The Early Successes Against Italy (to May 1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-845740-65-3.

Further reading

- Lamb, Charles War in a Stringbag. Cassell and Collier Macmillan (1977) ISBN 030429778X

- Lowry, Thomas P & Wellham, John W.G. The Attack on Taranto: Blueprint for Pearl Harbor. Stackpole Books (1995) ISBN 0-8117-1726-7

External links

- Battle of Taranto from Royal Navy's website

- La notte di Taranto – Plancia di Commando

- Battle of Taranto

- Order of battle